More about: The Coral

When you're a band of brothers and rock veterans who've survived the game longer than most, the peaks of your career may seem long behind you. But for The Coral, there's still one hell of a thrill in the chase - whether headlining festivals, supporting The Stone Roses or conquering Europe.

This year saw them release their first album in six years, the effervescent and genre-bending Difference Inbetween. Two decades into their career and still riding high at their peak, they remain a force to be reckoned with.

To celebrate the fine form they're in, The Coral's keyboardist Nick Power shares with us a tour diary - from the experience of playing with The Stone Roses at The Etihad Stadium to tearing up the European festival circuit.

BEAUTIFUL THING

It's a surreal experience, trundling beyond security gates into the Etihad stadium, seeing the roof of the enormous stage and the tiers of sky blue seats reaching up toward the sky like the frame of a huge empty cauldron. It can get the butterflies moving in a person's gut, if you know what I mean.

I loved the Stone Roses as a teenager. I'd obsess over the lyrics to 'Waterfall' and 'Made of Stone' and 'Where Angels Play'. They were like old poems, I thought, full of Brigantine sails and twisted grills and holy shrines, but with a street-smartness too. There were politics and art in the mix, a revolutionary undercurrent that never crossed over into preachiness. A certain mystery lay at the core of the Roses, and like them or not, they cooked up some alchemy around that first record that few have been able to touch. For me, the strange shimmer of Fool's Gold encompassed everything they were about. Like some skewed version of American desert noir, but for the north-west of England.

In a canteen in the bowels of the Etihad, I eat a good dinner. Better than I'd eat at home. As a rule, the bigger the gig, the better the catering is, for the most part. On a table opposite, Public Enemy sit waiting for their food. Even in private moments they have that militancy about them. Clad mostly in black, they talk quietly amongst themselves. Chuck D and Flava Flav at opposite ends of the table, as if they're about to call some meeting of grave importance. I suspect that they always come across like this. They're one of the most important bands of all time if you ask me.

Anyway, there's no chance of me going over to say hello. No chance. I'm-tongue tied at the best of times, so I'm happy to observe them from a distance. Though one of our mates, Jay Redmo, thinks he's left his rucksack underneath their table. Without hesitating, he walks over and starts rifling between where they're sat. I'm not sure Public Enemy understand a word he's saying. Either that or they think he's a cleaner. It's a brilliant scene.

We climb back to ground level and catch the end of The Buzzcocks. The stadium is brimming with people, even at this early point. The crowd are superb for us. There's usually a sense of detachment when I play gigs this size, but I feel every second of this one. I pick out a couple of people I know in the crowd, and suddenly I'm seeing this album cover in my head. I think it's Neil Young's 'Time Fades Away'. I'm picturing that, for some reason.

Public Enemy nearly bring the stadium to its knees. The bass feels like the aftershock of an earthquake. We hearit from our dressing room directly behind the stage. We're well into drinking the generous rider by that point and by the time the Roses take to the stage, we've inexplicably ended up at the other end of the stadium, watching bright red flares ghost into the night sky, the heave of people moving like a great sea.

One thing I noticed about the first Stone Roses reunion was that even in the huge venues they refuse to play like a stadium band. The delicacy is still there, the groove, the quiet moments. It takes a certain amount of defiance to retain that, I think. Guts, too.

I'm watching people mill out of the stadium now. The huge floodlights have illuminated and everything is bright suddenly. I'm behind the stage again, drinking Guinness with Steve Diggle of The Buzzcocks, our dressing rooms next door to one another.

We get to talking and Steve tells me about the time in the mid-nineties when The Buzzcocks toured with Nirvana. He said that they'd been using these old televisions as stage props, and Steve would smash them at the end of every gig. The way Steve told it, Kurt Cobain was interested in nicking the idea for Nirvana's set up. There was a moment in a soundcheck where Steve was teaching him the correct way to smash a TV without electrocuting himself. There's a knack to it, he said. Steve told me that Kurt never got to try it himself because the next week he'd shot himself, and they'd had to cancel everything and fly home. It was a sad time. I told him I was unaware they'd even played with Nirvana. Steve and I arrange to meet, maybe, when The Buzzcocks are in Liverpool next month.

We say our goodbyes and navigate our way down through the labyrinths of corridors and stairwells that lead to the outdoor car park. Soon we're in a fleet of black cabs, grinding down the M62 toward home.

In a strange way, the whole year seemed to coalesce to this point. Everything went off without a hitch, bar the over-eager door steward trying to bar me entry back into the stadium earlier to watch Public Enemy. I didn't have the right wristbands, apparently. Apart from that, it was a flawless night. Too perfect for this diary, quite possibly.

Manchester, 17/06/16

DINAMO ZAGREB

When we lose our minds, it's a collective thing. We completely go. All of us, off the deep end. Synchronised. Something bottlenecks and then releases in some spectacular disgrace. A kind of freefall.

This is my first time in Eastern Europe. On my way through customs, I'm pulled aside by airport security. A stocky man in a white uniform asks me if I'm carrying any drugs. He goes through a long list of narcotics and I shake my head at each one before he stares at me intently for a good twenty seconds. I almost expect him to ask well, do you want any then?

Zagreb is rainy and dull today, which is in direct opposition to everything I've heard about Croatia. We're all in shorts and sunglasses and ready for a mooch around the bars and restaurants of the city. Still, navigating down the wide Zagreb streets with endless arpichelagoes of distant tower blocks glassing the sky is a good dose of sightseeing in itself.

After a day and night in the hotel drifting in and out of sleep, watching loops of dubbed Steven Seagal movies that seem to play on every channel, by the next morning I feel ready to go.

We soundcheck early in the muddy, flooded field. The backstage area is sort of a partitioned gazebo with the names of the bands gaffered to each temporary room - Henry Rollins. Pennywise. Jake Bugg. Django Django. The Coral.

Our room has been stocked with a Croatian lager called Ožujsko. Crates of the stuff. There's nothing much else to do except sit around and drink it, until we go on to a small crowd that swells to a mob as the set builds.

Afterward, the backstage is full of artists. Some I recognise and some I don't. Jake Bugg keeps himself pretty isolated. He's had a hard time with the press recently and a part of me wants to say hello. I'm not sure why; I'm just aware how tough it must be fronting a thing on your own when you're as young as he is.

Pennywise are an American punk band who I know nothing about and suspect never will. Django Django I'm hoping to catch later- they play across the park from us, on the 'World Stage'. Outside, in the smoking area, Henry Rollins stomps around the temporary wooden boards that have been laid on top of the wet, boggy ground. He looks serious.

.jpg)

I'm floating around the festival now. It's late and I think I catch part of Django Django's set. I'm not entirely sure if I'm honest - there're pint glasses of vodka orange in each of my hands and I've worked through one of them already. It's been a long day.

At the furthest reaches of the festival, I'm drawn toward something called the Tesla Tower; a hundred foot-tall structure which is a direct reproduction of Nicola Tesla's 1901 Wardenclyff tower - built and designed to transmit messages across the Atlantic using the earth's own electrical charge. It was never completed. This imitation transmits David Bowie songs from small speakers at its base. Kind of a double-homage with a link: Bowie played Tesla in the movie The Prestige. It stands enormous in the field like some kind of holy monolith, lit by shimmering emerald green lights that run along its skeleton frame.

I'm down at the bottom, splayed on a cluster of rocks, trying to light a cigarette. There's a point where I feel myself float slowly up to the top of the tower. Seriously. I'm hanging there in mid-air as 'Let's Dance' plays from ground-level.

I see the flood of people below me move like tiny ants. There's a feeling like I've got seven eyes, each one peering out from the bass drum of every band playing on each of the seven stages. As if I can see and hear everything at once. Some high electric current running across the bones of the earth and through me, into the ether. The song I can hear now is 'Sound And Vision'.

Back in the dressing room, things have built to a fever. There's a chant going on - from inside and people outside - and it's hard to know where it started or what it means. But everybody seems to have picked up on it: "Das, Gras, Pumpen-funf. Das, Gras, Pumpen-funf", as if some demon were being summoned from the bowels of hell. Everyone has that look in their eyes; the X-ray look that thinks it can penetrate walls, but can't see five centimetres past its own nose. The chant goes on - "Das, Gras, Pumpen-funf".

We roll on like that for 45 minutes at least, the incantation gathering weight, the whole room shaking, and one of us falls clean through a wall, and I feel myself crying with laughter, wiping tears from the corners of my eyes with my sleeve.

Somewhere amongst the melee, one of us offers Henry Rollins (who isn’t happy about the noise) if he wants a blast on a joint, which apparently doesn't go down too well. Soon after, we're bundled into a van and back at the hotel.

I fall to sleep listening to a gang of Dinamo Zagreb fans singing in the street below the open window of the hotel room. It's a strangely comforting sound.

In the morning I wake up and realise everyone has left for the airport, everyone except for Alf from The Sundowners, who came along with us as a last minute guitar tech. He has a taxi waiting for us both. I probably only made the flight because of Alf.

When I arrive home I realise I've left most of my clothes, my deerstalker cap, comics, underwear and wallet at the hotel and I'll probably never see any of them again.

Zagreb, 20/06/16

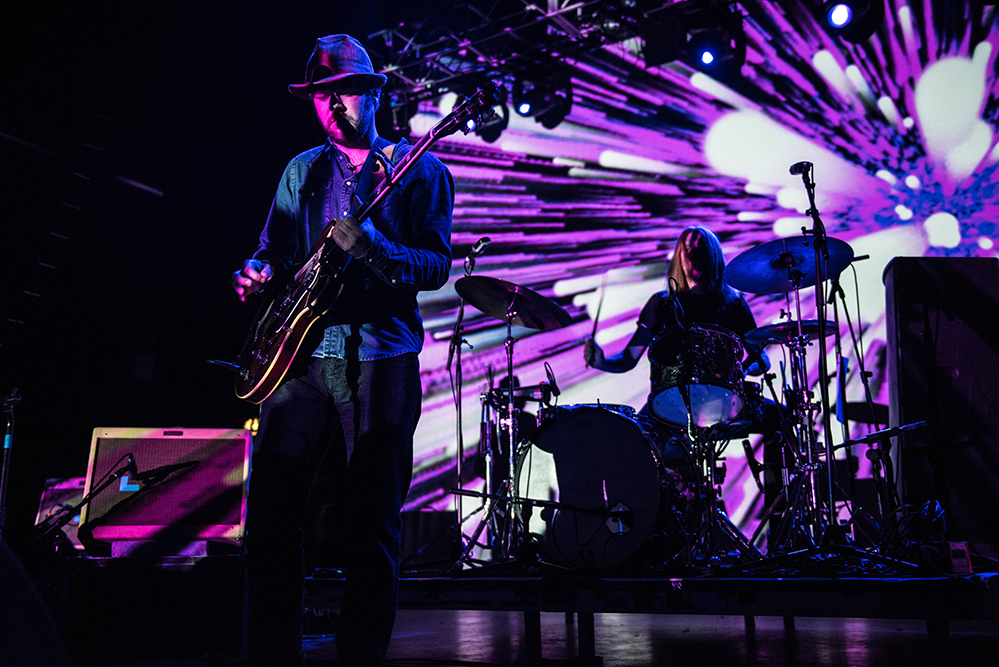

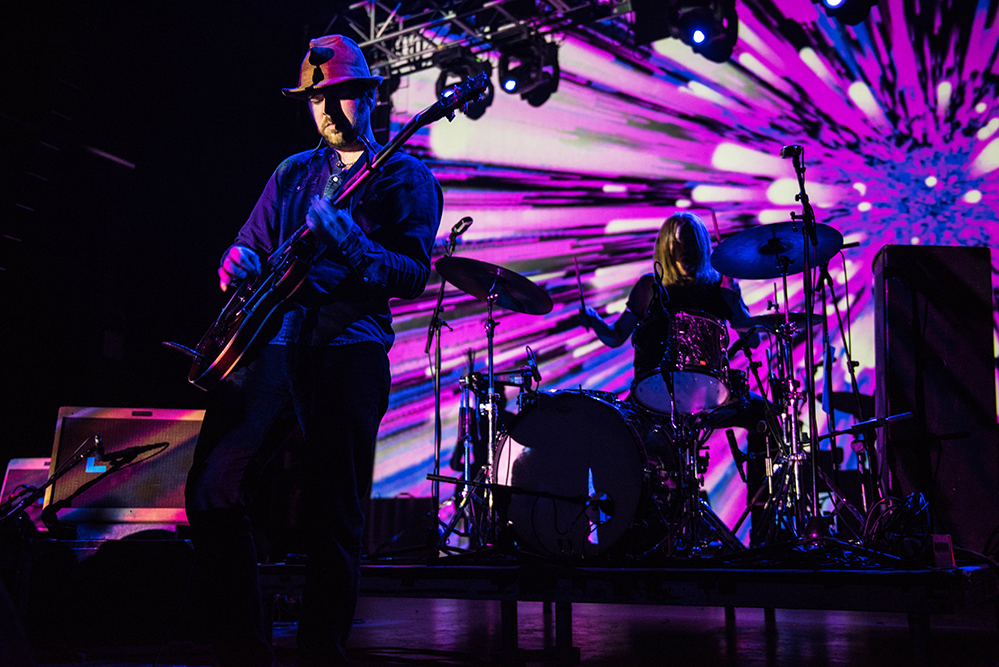

The Coral's London Forum show in brilliant photos

The Coral's London Forum show in brilliant photos

The Coral's London Forum show in brilliant photos

The Coral's London Forum show in brilliant photos

The Coral's London Forum show in brilliant photos

The Coral's London Forum show in brilliant photos

The Coral's London Forum show in brilliant photos

The Coral's London Forum show in brilliant photos

The Coral's London Forum show in brilliant photos

The Coral's London Forum show in brilliant photos

The Coral's London Forum show in brilliant photos

The Coral's London Forum show in brilliant photos

The Coral's London Forum show in brilliant photos

More about: The Coral