Photo: Press

Photo: Press

Today marks one of rock music’s saddest and most significant anniversaries. On 1 February 1995, the Manic Street Preachers’ principle songwriter and rhythm guitarist, Richey Edwards, left his hotel in London, packed suitcase abandoned behind him, and disappeared. He was not seen again.

Thedevastating effects of Richey’s disappearance are well documented. James Dean Bradfield, Nicky Wire and Sean Moore were not just his band-mates, they were his mate-mates, friends since they were teenagers just learning how to be in a rock band. Despite not being much cop as a guitarist, Edwards was more than just a lyricist: he also played a role alongside Bradfield in driving the band’s sound from the glam rock of Generation Terrorists to the nihilistic post punk of The Holy Bible. Lesser bands and greater bands than the Manics alike might have folded.

As it was, the band stayed together and the band changed. Their music softened and keyboards and strings came to prominence in it for the first time. Edwards wanted “to walk in the snow and not soil its purity” and the band paid tribute to him with a more delicate sound. They paid tribute to him with what is, in this writer’s humble opinion, their greatest album.

Everything Must Go was the album that introduced me, 10 years old when it came out in 1996, to the Manic Street Preachers. As I drifted through my teens I didn’t pay much attention to them beyond hearing their songs on the radio and – bizarrely – in a student nightclub while at Lancaster University. I was, according to a friend, “a singles whore” but I was far from alone.

To the British public, ‘Design for Life’ remains the Manics’ best known song. The escapist ‘Australia’ has a riff instantly recognisable off the radio and anyone whose first instinct is not to scream “HAPPY!” at the top of their lungs when the album’s title track comes on has no soul. For the first time in their careers, the Manic Street Preachers had reached out beyond the punks, the NME readers and whatever the early 90s version of a hipster was. Tongues planted firmly in cheek, they said that Generation Terrorists would sell 16m copies “from Bangkok to Senegal”; suddenly they were known as contemporaries of bands who did just that.

But good god imagine what the band was going through in the year between their friend’s disappearance and these anthemic songs proving popular on commercial radio. Imagine what was going through Wire’s head when he apologised to fans on the title track: “I just hope that you can forgive us, but everything must go”. Imagine the heartbreak Bradfield must have felt putting music to the lyrics Edwards left behind on ‘Small Black Flowers that Grow in the Sky’, ‘Kevin Carter’ and ‘Removables’. Imagine performing those songs to thousands of new fans who had discovered something that was immense fun to sing along to and were wholly unaware of the tragedy behind them. Everything Must Go is 20 years old and it is only in the past couple of years that I’ve really immersed myself in the Manics’ music and come to realise their brilliance; in retrospect, and in context, there are few more heart-rending albums.

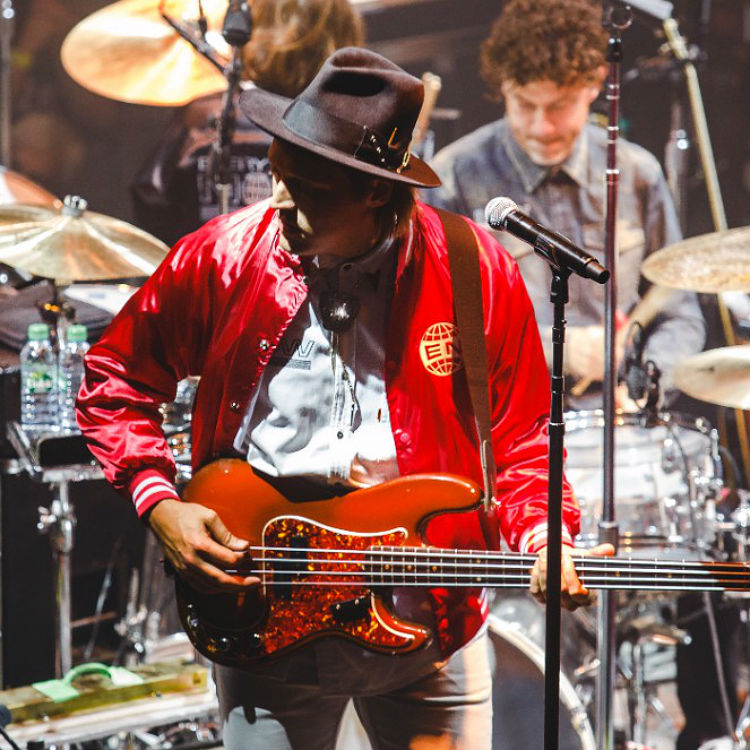

Last year the band took Everything Must Go on the road to celebrate its 20th anniversary. The tour was a celebration and that was apt. At the Royal Albert Hall the closer, ‘No Surface, All Feeling’ was accompanied by glitter fountains and streamers descending from the roof. As desperately sad as the lyrics are, Bradfield’s music is uplifting and anthemic. The album was performed in full and done so with verve and energy, Moore’s drumming freer than it ever had been and Bradfield launching into his guitar solos with the gusto of a man who has finally come to accept that this is the best thing he has ever done. Rather than mourning the loss of Edwards, it was, and the album is, a celebration of his life.

Richey Edwards was one of the finest lyricists of his generation. He was an unashamed literature nerd, who was “stronger than Mensa, Miller and Mailer” and “spat out Plath and Pinter”. He was “the virgin tattered and torn”. He forewarned us about consumer culture on ‘Motorcycle Emptiness’ and the dangers of “death sanitised by credit” on ‘Natwest Barclays Midlands Lloyds’ 16 years before the 2008 financial crisis. He was a feminist in 1992, damning the patriarchy: “You are pure, you are snow, we are the useless sluts that they mould”.

His disappearance and, officially since 2008, death is the tragedy here. That it led to the greatest moment in a great band’s career, though, is the emotional gut punch. “I just hope that you can forgive us”. If your heart doesn’t go out to Wire at that moment, it's up to the Manic Street Preachers to forgive you.