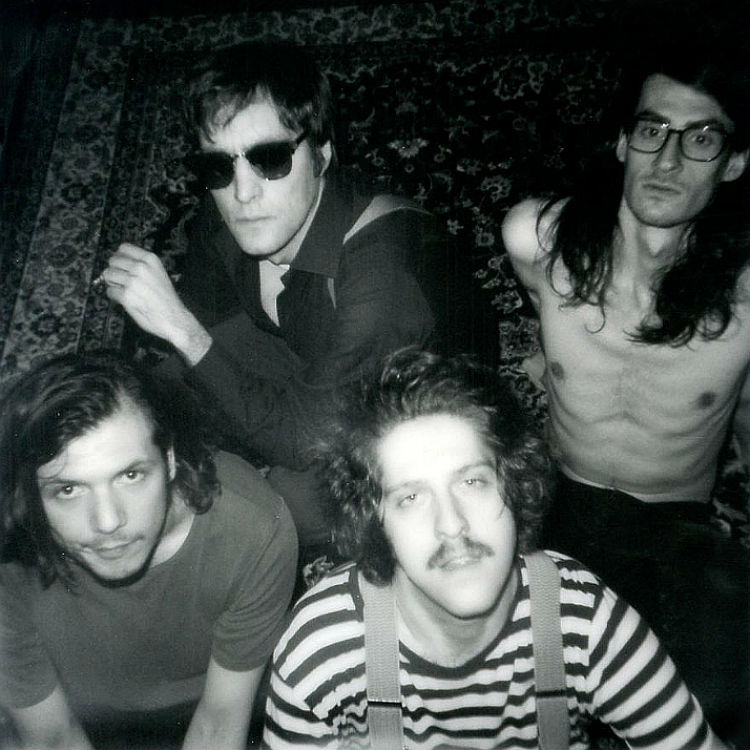

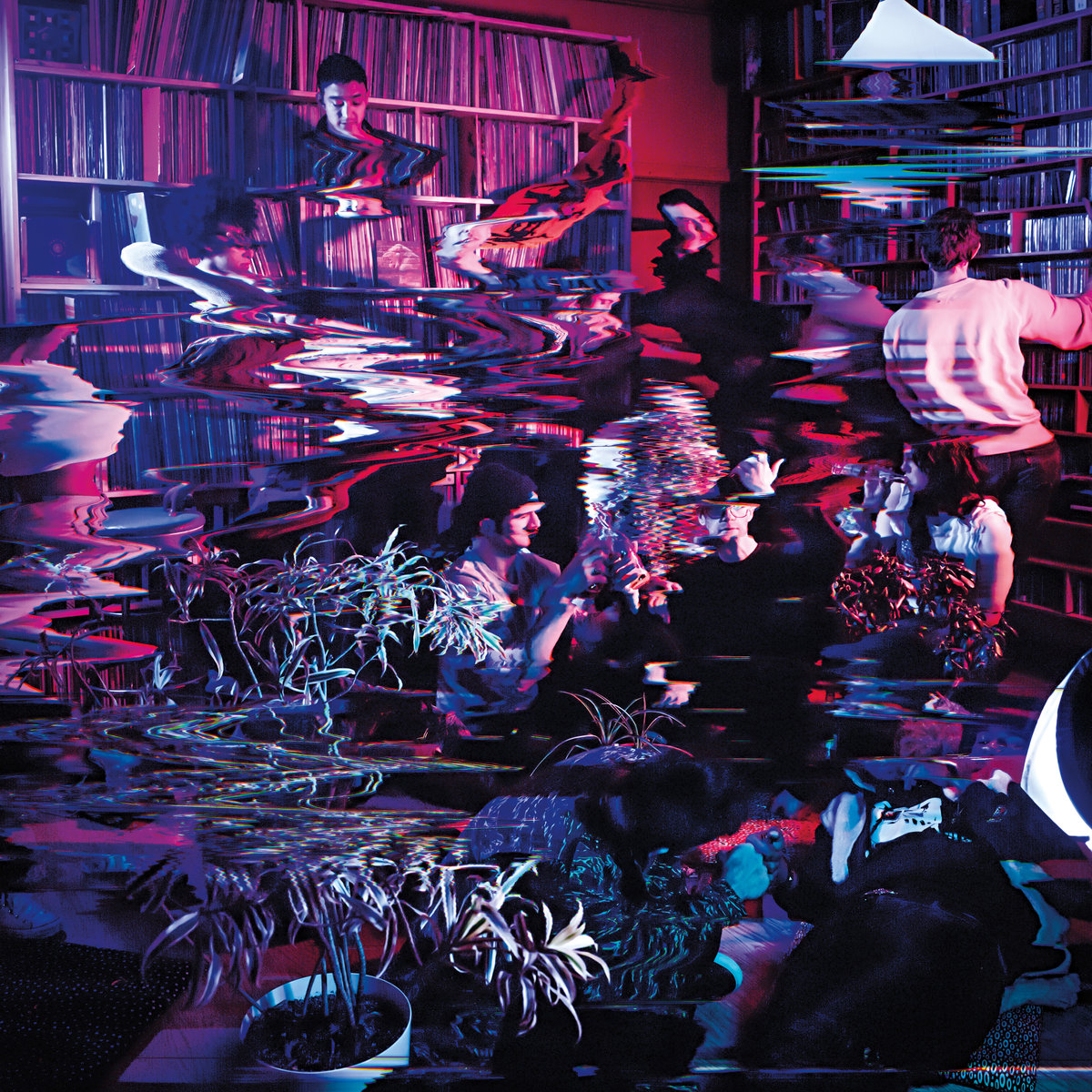

Photo: Mark McNulty

Photo: Mark McNulty

Synth-pop pioneers OMD returned with their stunning 13th studio album, The Punishment Of Luxury, last week. It sees the band push themselves into a glitch-y electronic world they’ve not previously trodden, whilst maintain that balance between sonic wormholes and pop perfection that has been a staple of the OMD experience.

Most people's love for OMD stems from the sheer joy of hearing their enormous hits, ‘Electricity’, ‘Enola Gray’ ‘Joan Of Arc’ - and many more that are too numerous to name. The band's innovative, original approach that questioned the very foundation of what was acceptable musically saw them blend their Kraftwerkian melodies with glam rock and pop and has been of inspiration to massive artists to emerge the last 40 years – including U2, Depeche Mode, The Horrors, Pet Shop Boys, a-ha, Erasure, Radiohead

The group started in the late 70’s after meeting at school and shared progressive ideas of where to take popular music buoyed by a love of synths, Kraftwerk, and inventing their own instruments from sheer poverty. The duo crafted a sound that stayed true to their beliefs that progress and a sound that could represent the future was important.

It wasn’t long out of school that they’d land a record deal with Manchester's Factory Records. After one single with Tony Wilson, who recognised their natural ear for pop-hooks and saw them as a band capable of dominating the mainstream, they were on their way.

Wilson's foresight helped them sign a record deal with Virgin for 7 albums – 5 of which went top 10. The band released a further three albums on the label but this time Paul Humphries ducked out to make music under a different name,leaving Andy McCluskey to be the only ever sole constant member of the group.

OMD split in 1996 and McCluskey recognised it was dating, he invented Atmoic Kitten in order to fulfill his relative ambitions and prove he could still write bangers. After making a small fortune, he recognised girl bands well and truly now out of fashion and his true love OMD reformed in 2010.

With the third album of the second era of OMD in full swing, we caught up with McCluskey getting to hear about the thought process behind a few of the tracks and a few other things; indlucing, coming to terms with post-modernism, the best new avant-garde releases, the poverty-stricken early days, working on Atomic Kitten. Read our exclusive interview below:

Gigwise: Hello Andy… It’s been four years since you had a studio album out. Any reason in particular you’ve taken your time? Just striving for greatness?

AM: The first 12 months we didn’t really do anything because we were having a little bit of a reassessment. Our drummer Malcolm, who had worked with us since the 70s, had a cardiac arrest on stage in Toronto towards the end of a long tour. Although he survived, it did make us stop and think.

The other thing is, particularly when you do try and make quality and challenge your own methodology, the reason we started OMD was to try and do something different, to not be clichéd and repetitive so if we want to make a record we want to make one that stands on its own two feet, that is not some pastiche of our former selves, but is also still lyrically and musically doing something that makes us interested. You’re basically undertaking a musical experiment and by that nature 9 out of 10 experiments fail musically.

G: What chimed on this one?

AM: Finally started to use some glitch sounds which we’d been wanting to incorporate but we found it hard to make them musical and bear repeated listening. But we did manage to do that on a couple tracks. Also to find something of interest, if you want to write about something you haven’t written before. I wanted to write a song called ‘Art Eats Art’ for some time because I’m aware we live in a post-modern era where most popular culture is consuming its own history. But to try and find a way to do it that actually worked was a challenge. That song had been written and re-written over several years.

G: I remember you said in 2012 in an interview with Contact Music: “Pop is eating itself as predicted, so basically it just feels like the decline and fall of the Roman Empire, and it's terminal.”

AM: I went through a long period of adjustment to the reality of post-modern culture. Because, when I grew up everything seemed to go in a direct timelines; where the new replaces the old and so when we got to the 90s and bands started wanting to sound like the Beatles again and using guitars, those who championed electronics were like, ‘ya what?’ You’re going backwards. But I start to realise it’s incredibly difficult now to make music that’s not been done before. You add that to a music industry that’s struggling to make profit therefore it’s been very conservative and safe.

G: There’s a lot of new German releases especially coming from the label Bureau B that seem to be original and musical, to me.

AM: I’m always interested in people doing new things. Do you know Uve Schmidt who releases record under the name Atom TM? His early albums were collections of noises that should be rejected: Crackles, pops, bangs, distortion. It was ok but you didn’t want to listen to it too often. He’s brought himself back with more musicality about four years ago with an album called HD and it inspired us for the new album. In particular, there’s a track on our new album called ‘As We Open So We Close’ which begins with quite fractured and dysfunctional music then the instruments glue it together and then it becomes dysfunctional again at the end, falling back into its glitch mess. We seemed to manage to make it work and retain musicality.

G: Talking of trying new things, the lead single ‘La Mitrailleuse’ sees you making beats from bullets which was quite interesting.

AM: It was inspired by a painting from the First World War that totally mechanised slaughter and I wanted to see if I could reflect that juxtaposition of humanity and the mechanism of the machinery. I was really excited. I’m used my human voice as a foil for a beat completely made out of artillery and gunfire. It’s like, 'OK Andrew now make that actually tolerable to listen to'.

G: I think you achieved it. What's ‘Robot Man’, also taken from the new album, about then?

AM: ‘Robot Man’ is initially conceived as the song of someone who has had therapy and decided to take off their armour and to be dare to be vulnerable and reach out. But we’re in an interesting juncture where computer and robotic algorithms are so complex that a lot of humanity is going to lose their jobs to the machinery because they can do it better. Biomechanics is going to be a very interesting subject in the next few hundred years. It’s going to happen, we are going to genetically try and modify ourselves. We are going to start adding machinery to ourselves so we do become somewhat biomechanical.

G: The album's title The Punishment of Luxury is taken from the Giovanni Segantini painting, It’s quite a serene painting on the surface. Can you explain what you got from it?

AM: It looks rather blissful, but actually it’s a painting of bad mothers in purgatory. It’s a misogynist painting from a later Victorian who wanted women to have their rightful position and not ideas above their station.

I appropriated the title for my own use in terms of the fact, most people in the modern Western society are materially better off than ever before because we’ve been brainwashed into thinking unless we have this, that and the other that we’re not worthy of love or self-respect. Marketing people are propagating and feeding our insecurities. They are trading on our worst anxieties in order to sell us stuff we don’t need.

G: Turn the clock back a bit. I’m curious, how did you learn music?

AM: We taught ourselves, we never had a music lesson in our lives other than being thrown out of the recorder group primary for miming because we’d rather play football. Later on I had a bass guitar that I bought with all the money I could blag off people for my 16th birthday, and it was left handed, it was the cheapest one in the shop. I learned to play upside down.

Paul had nothing. The reason we got together musically was he had built himself a stereo from scratch because he couldn’t afford to buy one, he studied electronics and he used to cannibalise radios for the components and build things that made noises which we then fed through friends fuzz boxes and echo units because we had absolutely no money.

G: How did this impact on the sound?

AM: The sound of OMD was determined by the only instruments we could afford to buy, Paul made an electronic drum kit that we used on our first recordings – you could trigger the individual sounds. We had a cheap Vox Jaguar organ which was the chords, we had a thing called a Selma Pianotron, which if you listen to our first single ‘Electricity’ that’s where the sound came from. The organ cost 30, the Pianotron cost 25, and the first synth we bought after our 6th gig, was a Korg Mircro preset that we got from a mothers catalogue for £7.76 for 36 weeks, and that is all we had.

G: After OMD spilt up but continued your pop career and invented Atomic Kitten. How did that come together?

AM: I invented Atomic Kitten because I was frustrated and conceited enough to think I could still write songs and it was only perceived out of the datedness of the vehicle that was holding me back. I joke with people that Kraftwerk invented Atomic Kitten. I became friends with Karl Bartos and I told him I was banging my head against the wall and I’d written a great song called ‘Walking On The Milky Way’’ and I suggested I could write for other people.

He said don’t do that then you’re just a prostitute and you’ll get your work messed with. Create a vehicle for your songs. The best pop vehicle in the world, a three-piece girl band. All the best manufactured pop is boy girl bands. Boy bands are shit they get away with murder because girls have the poster on the wall they’ll buy any crap. No girl ever had a hit with a bad song.

G: After Kitten I heard you worked with model and Peter Crouch's wife Abbey Clancy?

AM: When I stopped working with the Kittens Abbey came knocking on my door and in an effort to send her away I said I’m not working with a solo artist. She was 16 then, she came back two weeks later with two girls and she auditioned in the clothes shop she was working in on a Saturday afternoon. They were amazing, they could sing better than the Kittens and they looked stunning and the music,- we made an album with them - was way better than the Kittens. Stupidly I tried to get them a major deal and couldn’t because girl bands were out of fashion. Then Abbey realised there was a better living to be made of from dating a footballer. You know what she’s got one of the best voices I’ve ever recorded in my life - that girl can sing.

G: What new(ish) music are you into?

AM: I’m always listening out for stuff, there are some new bands, I do like Hot Chip, I really like a lot of what Robyn has done. I like Uve Schmidt, Atom TM. Some of the stuff Beyonce did a few years ago, the music was spectacularly dysfunctional with huge slabs of dissonant electronic synths. Love some of the early Gaga singles like ‘Bad Romance’, ‘Born This Way’.

G: Any collaborations coming up?

AM: I’d like to write some songs and get people to work on a guest album to get them to sing with us. Next year is our 40th anniversary and our old label want to do some milking of that which seems reasonable enough. I keep wanting to go forward. I don’t mind celebrating the past though, I like the different hats I’m allowed to wear.

G: Thanks for your time Andy.

Listen to some OMD, Atomic Kitten and some of McCluskey's favourite tunes below: