Photo: Press

Photo: Press

I'm about to spend my night somewhere very weird. I’m carrying a bag heaped full of pillows, blankets, and pyjamas through London Bridge station on a Saturday evening heading for an old fish market across the river, The Old Billingsgate Market. This 19th century market would have seen thousands of yards of fish pass through it every morning, but tonight the market plays host to something a little different.

Tonight five hundred people are here to experience Max Richter playing ‘Sleep’. Organised by the Barbican, the evening revolves around the composer’s 2015 album, with a performance of the full eight-hour piece, while people are free to drift in and out of sleep on the camp beds supplied.

It’s the second time the show has been in London, after previewing at the Wellcome Collection back in 2015. Since that point, the show has toured in Sydney and Berlin, with more performances due in Amsterdam and Paris. Despite this, performances of the full piece are still a rare experience, and tickets for the shows are snapped up very quickly.

When the album came out three years ago, the Anglo-German composer described it as an, ‘eight hour place of rest in a frenetic world,’ a piece to combat the struggle with insomnia so many of us face in cities. “The piece is to be slept through, it is a lullaby, but it is also an experiment in the way that music and consciousness can connect through this other state,” says Richter.

Richter is not the first to experiment with this sort of work, but he is one of very few who has managed to develop the narrative of sleep-based music past CD’s of whale music you find in discount high street shops. Richter also placed an emphasis on seeking advice from scientists working in the field during the composition of the piece, notably talking to the neuroscientist and author David Eagleman, to check the piece for adverse hallucinogenic effects.

The queue outside the show is unlike anything I’ve ever seen. Hundreds of people are lined up with duvets shoved in Ikea holdalls, and pillows that spill out the side of backpacks. Without being in on the story, you could be mistaken for thinking Billingsgate Market was offering housing shelter. People out in the piss in town stop and stare, bewildered by the mass of people silently waiting for entry. The whole queue itself has a feeling reminiscent of wartime videos of people queueing to enter Underground air-raid shelters.

On entering we find ourselves in the main hall, where camping beds are neatly laid out across five different sections. There’s no allocations for beds, which leaves people running to find the perfect spot. There’s plenty of beds to go round, and most of the first twenty minutes is spent feeling out different spaces around the room. I choose not to opt for a bed directly behind a couple who are passionately kissing. I find another perfectly centered towards the stage, but as I go to grab my stuff I return to find it taken. Eventually, I find myself happily next to someone who’s in a similarly talkative mood.

We talk a little about why we’ve both come, and what interests us about the night. It’s the hot conversation of the queue, now spilling into the space itself. Neither of us really know what to expect and are full of questions, but before we can have them answered, a voice on stage tells us we’re about to begin.

Some make a mad dash for the toilets to change into their pyjamas and brush their teeth. Others rearrange their sleeping bags and duvets before climbing in for the night. I brazenly leave everything a little too late and find myself scrambling to get my sleeping bag zip to open without making too much noise.

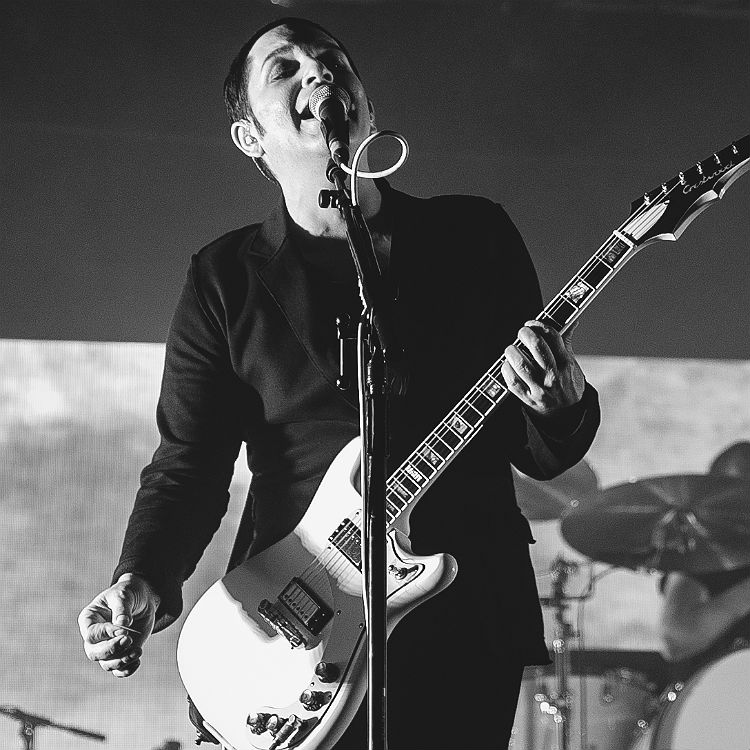

Richter appears after ten minutes. His introduction is brief and he says little other than to welcome people into the space. For all of us here, Richter included, the night is to be a deeply intimate and personal space to share collectively in the act of sleep.

The first few notes crackle from the speakers. Drifting slowly into a peaceful lullaby, Richter spends the first twenty minutes alone at the piano, before the strings enter. Some people enter a space that looks deeply meditative, rocking back and forwards with their eyes closed. Others sit upright. But most people choose to lie down.

In our single beds we are similarly alone and together. We are collectively being undulated by the sounds coming from the speakers, but the experience itself is one that is incredibly personal.

The space inflates a kind of voyeurism. The couple who were kissing earlier are now in separate beds, staring back into eachothers eyes. They have been separated by the rules of the space, but remain in sync. The women next to me, who was previously so talkative, now sits silently as she stares towards the stage. Richter himself is rocking back and forward with every drift of the piano. A cameraman pauses before taking a photograph, he is being careful not be intrusive, but it is a struggle not to be.

To see this far into people’s internal space is quite remarkable. I wrote last year about seeing Stars of The Lid at another Barbican show, about how I wished I could see the world people enter when they listen to ambient music, and here it is rendered almost visible.

Sounds wash past and the previously distinguishable piano fades into the background. So begins the poem of the night.

An hour in and most of the room now lie with their heads down trying to engage in sleep. Some toss and turn, others fidget in their camping beds, but all are silent. My brain still feels switched on and so I choose to draw some of the structures in the room. The drawing bends and eventually becomes a meditation on the music. In places it follows the erratic time signatures, at others it is calmed by the wash of strings in the space.

By hour two my eyes are drifting. I’m being seduced into slumber by the music. So I take a quick walk of the room before trying to get my head down.

Walking around, I notice some have bought camping chairs so they can sit up and watch the music all night. For some sleep forms no part of their plan. For others, they are out like a light, the music a backdrop to their dreams. I climb back into my sleeping bag and try to sleep.

My night’s sleep is scattered, and every hour I awake to different parts of the piece. At one point a soprano gently sings a lullaby. At another I’m woken by synthesisers carving a pattern in the reverberations of the piano. But it’s in the morning where I enter my deepest sleep. In the programme the last hour is described as a ‘Dawn Sunrise’ as the piece returns back to its beginning motif. It is here that I truly feel somewhere between consciousness and unconsciousness, the state that Richter talks about the piece wanting to conjure. The music enters my dreams and sends me into all areas of thinking.

In an interview with The Guardian, Richter describes more fully how our perceptions of the world can be changed by music. “For me, sleeping and music are both altered states; they are different ways of perceiving the world and relating to the world.”

For the final hour, the lights slowly fade back on, and for many sleep is broken. People sit up and stretch. Some walk around a little. The motif that began the whole piece slows down, before it all fades, and any distinction of sound is lost. A few carry on sleeping into the final moments, before being snapped back awake by the ripple of applause that follows after the final notes.

Applauding feels like a silly way to break the silence. For the last eight-hours we have been played something acoustically tuned towards feeding into a sleep stasis, and clapping breaks this spell. Many climb out of bed to give Richter a standing ovation. Me and a few others try to catch any last winks we can get before we are moved on into the London morning.

Almost instantly after the applause has ended people are rolling up their sleeping bags and packing away. The sleepover is over and all I want to do is lie in and think. Richter has helped us unlock something very different to any other performance I’ve been to. It’s a space for thought and contemplation. The space is one of exploration, but allows for us to drift without any focus whatsoever. For some that means remaining very attached in the physical and real, for others it means feeding into the hallucinatory space of dreaming.

As we wander out in the London morning, the rumble of conversation in the background is full of the pitter patter of people explaining their experiences to each other. It’s at this moment that what we’ve just finished feels truly communal, a chance to share in the wonder that the space of sleep has in all of us.